Double Dispatch

Tony Messias

I have been reading the book "Smalltalk Best Practice and Patterns", so I'm going to share some cool patterns in this blog. I shared this on Twitter:

Some cool design patterns I've learned recently:

— Tony Messias (@tonysmdev) May 8, 2021

- Method Object

- Double Dispatch (aka. Duet or Pas de Deux)

- Pluggable Behavior

🤓

And Freek Van der Herten mentioned that I could cover them as blogposts. Here's is the first one. Well, technically, the second one. See, the first pattern I mentioned there called "Method Object" was already covered here in this blog in the post titled "When Objects Are Not Enough". Same idea. Which is cool. I've updated the post to add this reference.

Now to Double Dispatch!

Introduction

The computation of a method call is only dependent on the object receiving the method call. Most of the time that's enough. However, sometimes we need the computation to also depend on the argument being passed to the method call.

Think you have two hierarchies of objects interacting with each other and the computation of these interactions depends on both objects, not only in one of them. Maybe some examples will make this clearer.

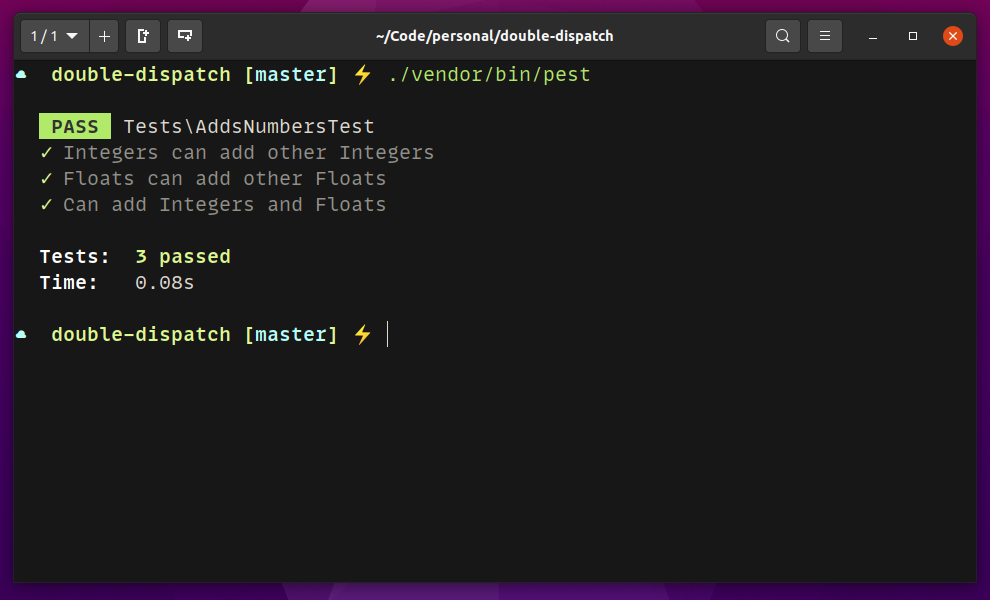

We're going to TDD our way through this pattern using Pest. Feel free to use whatever you want. All classes are in the same file as the test for the sake of the demo.

Example: Adding Integers and Floats

Let's get to the first example: adding numbers. For this example, let's imagine we are building the base classes for numbers in a language and that our language is not able to add primitives of the different types.

We'll start with the use case of adding only integers:

declare(strict_types = 1); test('adds integers', function () { $first = new IntegerNumber(40); $second = new IntegerNumber(2); $this->assertSame(42, $first->add($second)->value);});Let's add IntegerNumber class to the top of the test file to make the test pass (right below the declare() call):

class IntegerNumber{ public function __construct(public int $value) {} public function add($number) { return new IntegerNumber($this->value + $number->value); }}That works. Notice that we added a declare(strict_types = 1); to the PHP file. I did this because PHP is very smart and is able to sum integers and floats, so I wanted to force us to manually cast the values for the purpose of this example.

Let's add test for adding floats:

test('adds floats', function () { $first = new FloatNumber(40.0); $second = new FloatNumber(2.0); $this->assertSame(42.0, $first->add($second)->value);});And, to make it pass, let's add the FloatNumber class:

class FloatNumber{ public function __construct(public float $value) {} public function add($number) { return new FloatNumber($this->value + $number->value); }}Our tests should be green. So far, so good. Let's add our first cross-addition: adding integers and floats.

test('adds integers and floats', function () { $first = new IntegerNumber(40); $second = new FloatNumber(2.0); $this->assertSame(42, $first->add($second)->value); $this->assertSame(42.0, $second->add($first)->value);});OK, how can we get that one working? The answer is: Double Dispatch. The pattern states the following:

Send a message to the argument. Append the class name of the receiver to the selector. Pass the receiver as an argument. (Kent Beck in "Smalltalk Best Practice Patterns", pg. 56)

This was in Smalltalk. For us, the selector is the method name (or close enough). Let's apply the pattern. First, let's handle our first use case adding integers:

class IntegerNumber{ public function __construct(public int $value) {} public function add($number) { return $number->addInteger($this); } public function addInteger(IntegerNumber $number) { return new IntegerNumber($this->value + $number->value); }}If we run the first test, it should still pass. That's because we're adding two instances of the IntegerNumber class. The receiver of the add() message will call the addInteger on the argument and pass itself to it. At that point, we have two integer primitives, so we can return a new instance summing the primitives.

Now, let's make a similar change to the FloatNumber class:

class FloatNumber{ public function __construct(public float $value) {} public function add($number) { return $number->addFloat($this); } public function addFloat(FloatNumber $number) { return new FloatNumber($this->value + $number->value); }}Our first two tests should be passing now. Nice! Let's now add the cross methods. First, an integer only knows how to add other integers (primitives). Similarly, floats should only know how to add their own primitives. However, integers should be able to convert themselves to floats and vice-versa. This will allow us to add floats and integers together.

When a Float Number instance receives the add() message with an instance of the IntegerNumber class, it will call the addFloat on the argument, and pass itself to it. So we need an addFloat(FloatNumber $number) method on the IntegerNumber class. As we discussed, an IntegerNumber number doesn't know how to sum floats, but it knows how to convert itself to a float. And who knows how to add two floats together? The FloatNumber instance! So, at that point, the IntegerNumber instance will cast itself to Float and call the addFloat() on the float number instance with that. Then, the float number does the primitive addition and returns a new instance of a FloatNumber.

Similarly, when an Integer Number instance receives the add() message with an instance of a FloatNumber class, it will call addInteger on it, passing itself to it. Then, the Float Number will cast itself to an integer and pass that back to the integer calling addInteger. Again, at that point, Integer can do the primitive addition and return a new instance of an IntegerNumber class.

Here's the final solution for both the IntegerNumber and the FloatNumber classes:

class IntegerNumber{ public function __construct(public int $value) {} public function add($number) { return $number->addInteger($this); } public function addInteger(IntegerNumber $number) { return new IntegerNumber($this->value + $number->value); } public function addFloat(FloatNumber $number) { return $number->addFloat($this->asFloat()); } private function asFloat() { return new FloatNumber(floatval($this->value)); }} class FloatNumber{ public function __construct(public float $value) {} public function add($number) { return $number->addFloat($this); } public function addFloat(FloatNumber $number) { return new FloatNumber($this->value + $number->value); } public function addInteger(IntegerNumber $number) { return $number->addInteger($this->asInteger()); } public function asInteger() { return new IntegerNumber(intval($this->value)); }}

It works! Nice. If you're like me, you're now delighted with such a sophisticated implementation.

Isn't this cool?

Example: Star Trek

OK, the numbers example was cool and all, but chances are we're not implementing a language. Is this even useful anywhere else? Well, the important thing about a pattern is the design, not the implementation. You can re-use the same design on different contexts.

Let's say we're building a Star Trek game. We'll control a spaceship and there might be some enemies along the way, so they have to fight. Some enemies will be critical while others will not cause any damage depending on the spaceship.

So we have two hierarchies at play here: Spaceships and Enemies. And the computation of the combat depends on both of them. Perfect use case for the Double Dispatch pattern.

Let's start with a simple case: an asteroid and a space shuttle. The asteroid damages the shuttle, but not critically:

test('asteroid damages shuttle', function () { $spaceship = new Shuttle(hitpoints: 100); $enemy = new Asteroid(); $spaceship->fight($enemy); $this->assertEquals(90, $spaceship->hitpoints);});The implementation would be something like this:

class Shuttle{ public function __construct(public int $hitpoints) {} public function fight($enemy) { $this->hitpoints -= $enemy->damage(); }} class Asteroid{ public function damage() { return 10; }}The test should be green. Nice. Let's add another spaceship. The USS Voyager should not receive any damage from an Asteroid.

test('asteroid does not damage uss voyager', function () { $spaceship = new UssVoyager(hitpoints: $initialHitpoints = 100); $enemy = new Asteroid(); $spaceship->fight($enemy); $this->assertSame($initialHitpoints, $spaceship->hitpoints);});Let's implement our new spaceship:

class UssVoyager{ public function __construct(public int $hitpoints) {} public function fight($enemy) { // Nothing happens. }}Our tests should be green now. Uhm... it looks weird, right? Let's add another enemy and see if it this design still works. Our new enemy is a Borg Cube. Borgs will assimilate any spaceship (resistance is futile).

Let's start with a test for the Shuttle facing the Borg Cube:

test('borg cube critically damages the shuttle', function () { $spaceship = new Shuttle(hitpoints: 100); $enemy = new BorgCube(); $spaceship->fight($enemy); $this->assertSame(0, $spaceship->hitpoints);});Let's implement the Borg Cube enemy:

class BorgCube{ public function damage() { return 100; }}OK, our test should be green. Let's add another test before we refactor this. Borgs will also assimilate the USS Voyager:

test('borg cube critically damages the uss voyager', function () { $spaceship = new UssVoyager(hitpoints: 100); $enemy = new BorgCube(); $spaceship->fight($enemy); $this->assertSame(0, $spaceship->hitpoints);});And... red. Tests are failing. That's because so far nothing damaged the USS Voyager. I think it's time to apply the pattern. First, let's send a message to the enemy, append the spaceship name to the message and pass it along as an argument:

class Shuttle{ public function __construct(public int $hitpoints) {} public function fight($enemy) { $enemy->fightShuttle($this); }} class UssVoyager{ public function __construct(public int $hitpoints) {} public function fight($enemy) { $enemy->fightUssVoyager($this); }} class Asteroid{ public function fightShuttle(Shuttle $shuttle) { $shuttle->hitpoints -= 10; } public function fightUssVoyager(UssVoyager $ussVoyager) { // Does nothing... }} class BorgCube{ public function fightShuttle(Shuttle $shuttle) { $shuttle->hitpoints = 0; } public function fightUssVoyager(UssVoyager $ussVoyager) { $ussVoyager->hitpoints = 0; }}If we extract an Enemy interface here, we would have something like this:

interface Enemy{ public function fightShuttle(Shuttle $shuttle); public function fightUssVoyager(UssVoyager $ussVoyager);}If we add a new enemy to the system, we know we only have to implement the enemy interface and it should Just Work™. Adding a new spaceship? We also need to add it to the enemy interface.

Conclusion

This is not always flowers and sunshine, though. There is a bunch of indirection at play here. The alternative would involve a couple if/switch statements around, so I think it's worth it.

You might think this is similar to the Visitor Pattern, and that's true. The Visitor Pattern solves the problem when Double Dispatch cannot be used (see the Wikipedia for Double Dispatch.) Also make sure to check out this video on the subject.

I had fun writing this piece. And I'm having a lot of fun reading the book. Let me know what you think.