The Secret Life of Programs (a book review?)

Tony Messias

I wanted to write about this book because it really got me thinking about my experience and my relationship with computers. I feel like this is going to be a bit personal, but I'm not entirely sure how this will end up.

I graduated in 2012 in System Analysis (4 years) and a few years later I returned to get a specialization in Software Engineering (2 more years). Counting by when I started college (2009), I have 11 years of experience in this field (holy sh*t). But that's not how I personally count. I got an internship in web development half-way through my graduation and was hired as a programmer 1 year later, around 2011. That makes it almost 9 years of professional experience. And I still struggle with impostor syndrome. It comes and goes, and I'm not really sure what triggers it yet.

Anyways, I started trying to beat this up and that's where this book enters. See, my graduation course wasn't deeply technical on how computers work. Instead, it was a mix of high-level, general concepts on programming (intro to programming, data structures, some networking, a few languages, databases), a bit of business stuff (management, accounting, sociology), and some math too (algebra, statistics, calculus). It wasn't computer science.

So I started looking for books to fill in some gaps that I don't even know I have (finding these gaps is part of the process as well). That's where I found The Secret Life of Programs book. And it's amazing. It goes from bits and electronics to logic gates and circuits, going up into data structures, then programming languages, and then how the browser works, then we get to see a Javascript program and its C version to understand the difference between high-level languages and low-level languages, then it touches on security and machine intelligence (machine learning + big data + artificial intelligence), and ends with some "real world" considerations. That's the gist of the book. I highly recommend it if you don't have a very "computer science" background, like me.

As much as I want to talk about all topics the book covers, it isn't practical (and probably illegal), but I wanted to share some learning and highlights I got from the book. Let's begin.

What is programming?

Right from the beginning, the author goes over the importance of low-level knowledge. He starts by saying he agrees with the definition of computational thinking by Stephen Wolfram:

formulating things with enough clarity, and in a systematic enough way, that one can tell a computer how to do them.

That's a very good statement. In order to write programs, we have to understand the problem (and domain) involved. Lack of knowledge about the problem (what to actually do and what we shouldn't care about) are directly projected into the codebase. You can see all the uncertainties about the domain in the code (sometimes even feel it). The author agrees with Wolfram's general idea but disagrees when Wolfram suggests that we don't need to learn "low-level" details.

One thought I've just had while writing this is that we try to add more and more constraints to our codebases as an attempt to make correct systems, but I think a better understand of the problem we are trying to solve (or improve) usually pays off better than any coding technique you might find out there. That's why ShapeUp and Event Storming can help, IMO. Anyways, back to the book review.

There is also a short definition of programming as a 2-step process:

- Understanding the universe; and

- Explaining it to a 3-year-old.

The difference between coding, programming, engineering, and computer science is also really good:

- Coding: the knowledge of some codes to make certain things (being able to "make the text bold" in an HTML page). Usually, a coder is proficient in one special area (HTML or JS, for instance);

- Programming: knowing more than one special area or two;

- Engineering: the next step up in complexity. To quote the author "in general, engineering is the art of taking knowledge and using it to accomplish something";

- Computer science: the study of computing. Often, programming is mixed up with computer science. Many computer scientists are programmers, but not all programmers are computer scientists. Discoveries in this field are used by engineering and programmers.

The author also makes an interesting comparison with doctors regarding generalists vs specialists. He says that in medicine a specialist is a generalist that picks one area to specialize. Whilst in programming, a specialist is someone that knows a particular area, but usually doesn't have a general understanding of the whole picture. He would prefer our field to be more like the medical field. I found this comparison interesting. It aligns with the idea of the T-shaped skills.

Talking to computers

The book spends almost half of its contents talking about very low-level details from bits to hardware. Although there were parts here that I wanted to skip (I noticed that I'm not very much into computer details, like the electronics parts) there was some really helpful stuff in this part. It goes over everything from what is a bit, to how can we represent negative numbers in binary, bit addition, and other operations. It's all very interesting.

The part about representing time in computers was really good. Humans use periodic functions to calculate time, like the rotation of the Earth (1 full rotation == 1 day), or the time it takes for a pendulum to swing in old clocks.

But computers work with electronics, so an electrical signal is needed as the periodic function. Enters oscillators and quartz crystals. The crystal generates electricity when you attach some wires to it and give it a squeeze. Add electricity to the wires and it bends (see this video and the following one for more info on how quartz crystals generate electricity.) So, in order words, if you apply electricity to a crystal, it will send electricity back to you, and this happens in a very predictable time schedule, making it a good oscillator.

He also goes into very low-level details on why we use binary in computers and how all the analog-to-digital conversion happens. There were some nice explanations on bit numbering. I found the naming really good "least significant bit" and "most significant bit" are called that because changes in the left bits result in bigger changes in the actual value (just like in decimal, if you change "11" to "21" you almost doubled the value while from "11" to "12" is a relatively small change).

He also explains "shift" operations in binary:

- Shift left: move all bits 1 position to the left, throwing away the MSB. Practically this multiplies the value by 2, but it's much faster than multiplying by 2 in CPU time;

- Shift right: move all bits 1 position to the right, throwing away the LSB. Practically, this divides the value by 2, but (again) much faster.

"0100" binary in decimal is "4" if you "shift-left" it becomes "1000", which converted to decimal again is "8". If we do a "shift-right" instead, the same binary number "0100" becomes "0010", which when converted to decimal becomes "2". Cool, right? PHP has bitwise operators, so we can see it in practice here:

$ php artisan tinkerPsy Shell v0.10.4 (PHP 7.4.7 — cli) by Justin Hileman>>> $a = 4;=> 4>>> $a >> 1;=> 2>>> $a << 1;=> 8Languages can optimize our code for us and decide when to use bitwise operators. So we can actually choose to write code for humans instead of writing it for machines almost all the time.

Compilers, interpreters and optimizers

The book explains the difference between these 3, I'll try to summarize it here:

- Compiled languages turn the source code (the high-level programming language we wrote) directly into machine code (opcode). Compilers do that translation. The machine code is usually generated to a specific target machine, that's why you need to generate binaries for Intel and AMD processors because the opcode on those architectures are different;

- Interpreted languages don't result in machine code (for "real" machines - as in "hardware"). They usually have a virtual machine as a target. It's up to the interpreter to either generate the opcodes from the directly from the source code or cover that source code to some kind of "intermediary" language that is easier to translate to opcode.

Compiled languages are usually faster, but these days computers are so fast that we can afford the luxury of using interpreted languages without many problems in most cases. That can't be said for embedded systems, where resources are usually scarce.

Optimizers can be used to, well, optimize the generated machine code. Here's Rasmus Lerdorf (creator of PHP) talking about compiler optimization in PHP. With optimizers, we can generate smarter machine code by getting rid of static, unused statements or by moving opcode around for the sake of optimization (like when you do a calculation inside a loop using values defined outside of the loop. The optimizer is able to detect that and move the opcode to generate the calculation to outside the loop for you.)

One interesting thing here is that I realized I considered Java to be a compiled language. But, according to the author, it's actually interpreted. There are some hints in the name of the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) but for some reason, it was sitting with the compiled languages in my mind. C and Go are examples of real compiled languages. Just because a language has a compiler it doesn't mean it's "compiled".

The browser

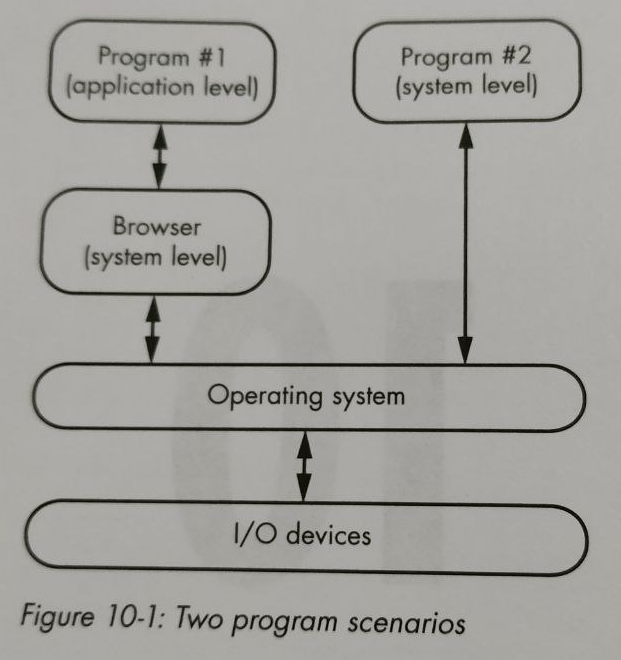

I felt like home in here. It goes over how the browser works, what is HTML, what is the Document Object Model (DOM), what is CSS, what is JavaScript, etc. Then it goes by saying that browsers are actually big interpreters.

Then it goes ahead and implements a game in JavaScript using the tree nature of the DOM itself to build a knowledge tree. After about 40 lines of JS code, the "guess the animal" game was done. He then writes the C portion of it, forcing him to explain I/O and memory management and all the low-level details that we didn't have to worry about in JS running in the browser. No need to say that the C version was longer, right? About 171 lines long.

Project management

After some more advanced topics, the book gets to a "real world considerations" chapter where the author talks about the short history of UNIX, dealing with other people, aligning expectations with stakeholders and managers, project management stuff.

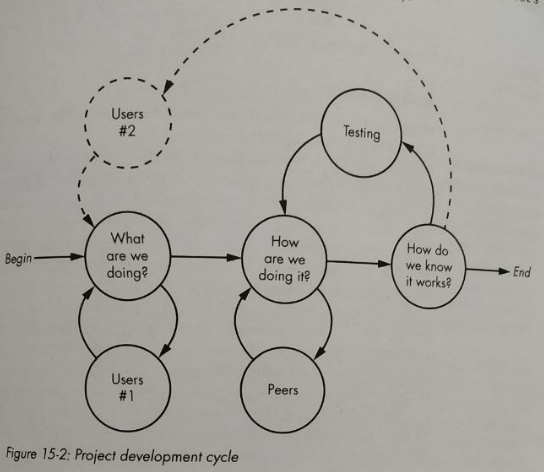

I really liked the development methodology section. He mentions that sometimes it feels like we are treating methodologies as "ideology". It's all about doing some rituals over and over and hoping to deliver the project on time and on budget. His advice was: don't take any methodology too seriously, as none of them actually work in their pure form. His chart pretty much summarizes all methodologies:

The project development cycle goes like this:

- Understand the problem you are trying to solve with the stakeholders;

- Figure out a way to build it internally, iterating over design decisions with your peers;

- Validate if you are heading in the right direction with your stakeholders again;

- Repeat until the problem is solved.

There were also some practical project design tips, like:

- Ideas start by writing them down. Don't code it right away, write them down first and try to fully understand the problem you are solving;

- Create prototypes, but throw them away. They don't have to be perfect, nor use "real implementations" of anything;

- Don't put a hard deadline on prototypes. It's usually creative work as we don't know exactly what we are prototyping, so it's hard to come up with a realistic schedule anyways;

He also mentions a bit about abstractions and how we should avoid having too many, and shallow abstractions. Prefer a few, deeper abstractions instead. He mentions the Mac API. The Apple Macintosh API set of books was released in 1985 with 1200 pages in total. And it's completely obsolete now. He suggests that one of the reasons could be because the Mac API was very wide and shallow. Compare that with UNIX 6, released in 1975 (10 years earlier), with a 312-page manual. The UNIX API was narrow and deep.

One example is the Files API. On UNIX almost everything is a file (or acts as a file). Other operating systems had different system calls for each type of file, but UNIX had a unified API (file descriptors). That means that you can use the UNIX cp command to copy a file on your local file system to a different location, or send it over the network via an I/O device (like sending a file to your printer, for instance).

Other topics

I only mentioned the topics that I found really relevant to me, but the book goes over way more topics than I cover here, like:

- Using math to cheat: how we can use math to compress images, draw figures on canvas, etc;

- Security: giving us a basic understanding of security in general. Touches on cryptography and some "not so easy to spot" threats;

- There is also way more hardware stuff than I mentioned here.

I also got a copy of "The Imposter's Handbook" that I'm going to be reading soon (I have some other books in the pipeline, like "The Design of Everyday Things" and "The Software Arts"). I just felt really excited about finishing this book.